Species Ireland has Lost

Before the last Ice Age Ireland was connected by land-bridges, one to Scotland and one to Wales. The Irish Sea was a large freshwater lake and it’s reasonable to assume that the country’s wildlife was similar to Britain’s at the time. Yet between 7,500 and 12,000 years ago rising sea levels flooded the land-bridges and turned the lake into a sea and Ireland into an island. In the Pleistocene era Ireland was home to hairy mammoths, woolly rhinoceroses and the Megaloceros, the giant Irish deer, the largest deer that ever lived. Almost all these animals and birds, both the ones that are globally extinct and the ones that are extinct in Ireland, are no longer with us as a direct result of human persecution, hunting and habitat destruction.

Ireland’s biodiversity remains under threat and may still lose many more species. Here are some already considered extinct in Ireland in more recent times.

Top 10 Spices that we already lost

×

Grey wolf

Corn bunting

Hornet moth

Solitary bee

Meadow saxifrage

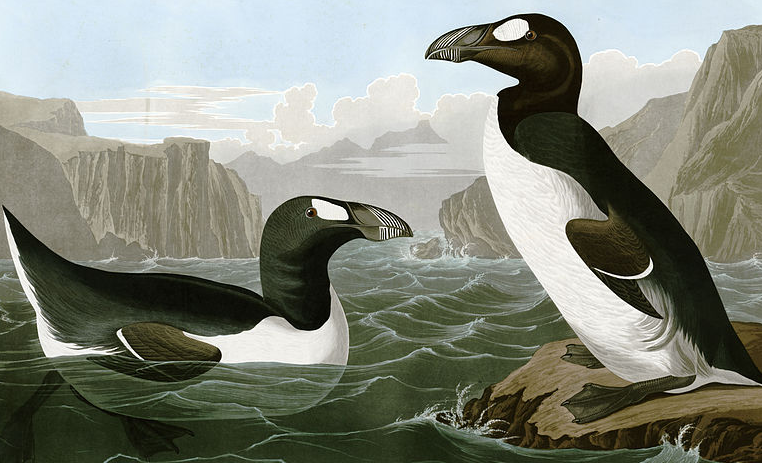

Great Auk

Holy grass

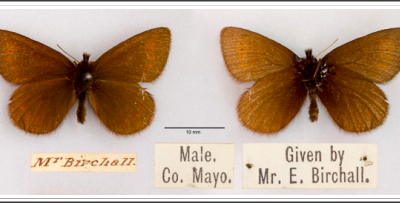

Mountain ringlet

Spiral Chalk-moss

Mud pond snail